何故戦ったのか?: あるA級戦犯容疑者の隠れたミッション(仮題)

This feature-length documentary film project, currently work-in-progress, challenges the commonly-accepted WWII narrative of Japan as an expansionist aggressor. Through exploring the untold histories of young Japanese “spies” including Co-director’s late father, the film introduces Dr. OKAWA, the “spy” school’s founder and an indicted class-A war-criminal, who fought against White domination in Asia.

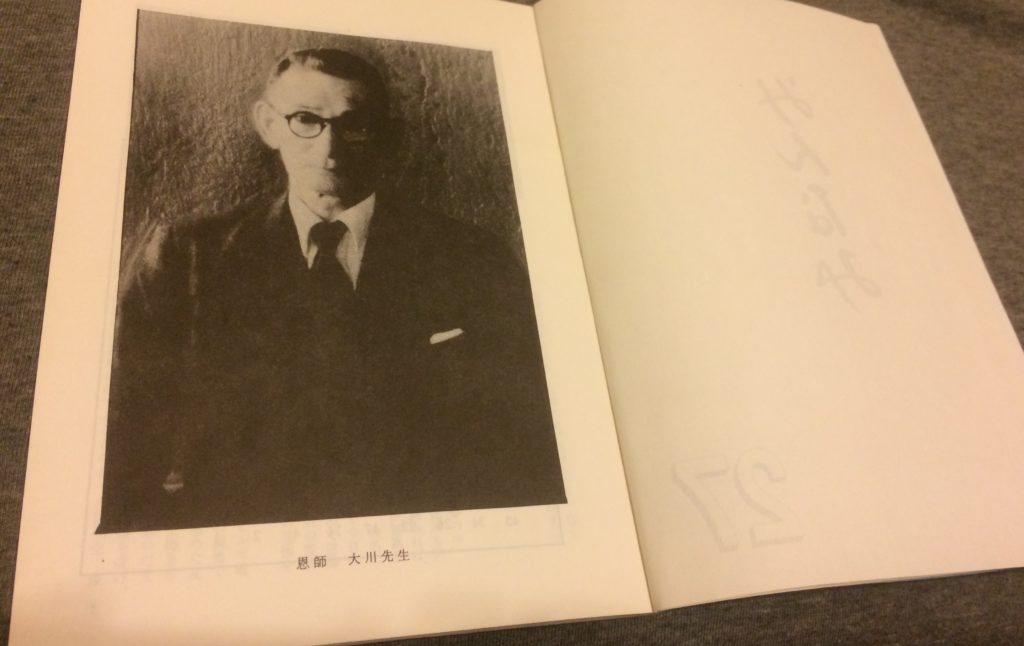

In 2007, we (Max Uesugi & Reiko Tahara) spent the summer clearing the house of Max’s late parents in Okayama, Japan. We each had emigrated from Japan to the U.S. in the early 90s, and lived in New York since. Max’s mom Satoko had passed away in 2003, and Max’s dad Hideo in 1996. Max was going to sell the house to ease our immigrant life in Brooklyn. Satoko had kept all of Hideo’s belongings as they were. After tearing and trashing an old graduation certificate for Hideo found in the back of the closet, Max noticed a stack of small colorful “zines,” tucked away under Hideo’s study desk, that mentioned the strange long name of an institution that the certificate was issued from. The zines talked about a number of well-known historical and controversial events in Japan – such as “the Tokyo Trial,” “Class-A war criminals,” and “5.15. Incident (a coup-detat in 1932 that arguably lead Japan to the militarism), ” and Hideo’s name was in the list of deceased members. Each volume opened with the same photograph of a Japanese man with huge eyes and big nose with the same caption: “Dr. OKAWA –Our Great Teacher.”

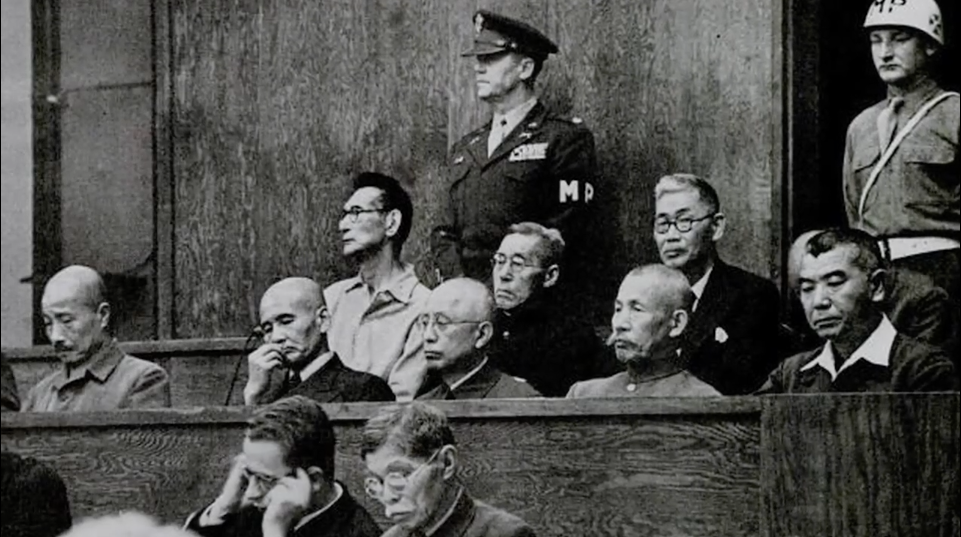

Although we had never heard of Dr. Okawa, we learned from a quick research that he was possibly the most influential theorist back then, and was the only civilian among the 28 indicted Class-A War Criminals at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (a.k.a. Tokyo Trial). The class-A war crime was a new crime created by the Allies after WWII and was called “crime against peace.” It was for the national leaders who led Germany and Japan to the unjust, aggressive war. There was a wikipedia page for Okawa (which has been since updated) that described him as an ultra-nationalist, Pan-Asianist, and Islam scholar, who was involved in the Manchurian Incident in 1931, a staged train bombing by the Kwantung Army that helped Japan’s “invasion” of Manchuria and building of Manchukuo. A year later, he agitated the young army officers in Tokyo, raised funds and provided pistols for the 5.15. Incident, and was imprisoned for five years for it. He published many inflammatory books and lectured widely. Based on those records, the Allies’ prosecutors considered Okawa to be among the braintrust of the military government and the father of the infamous “Greater Asia Co-Prosperoity Sphere” doctrine used by the Japanese army to invade Asia. They saw Okawa as Alfred Rosenberg of Japan.

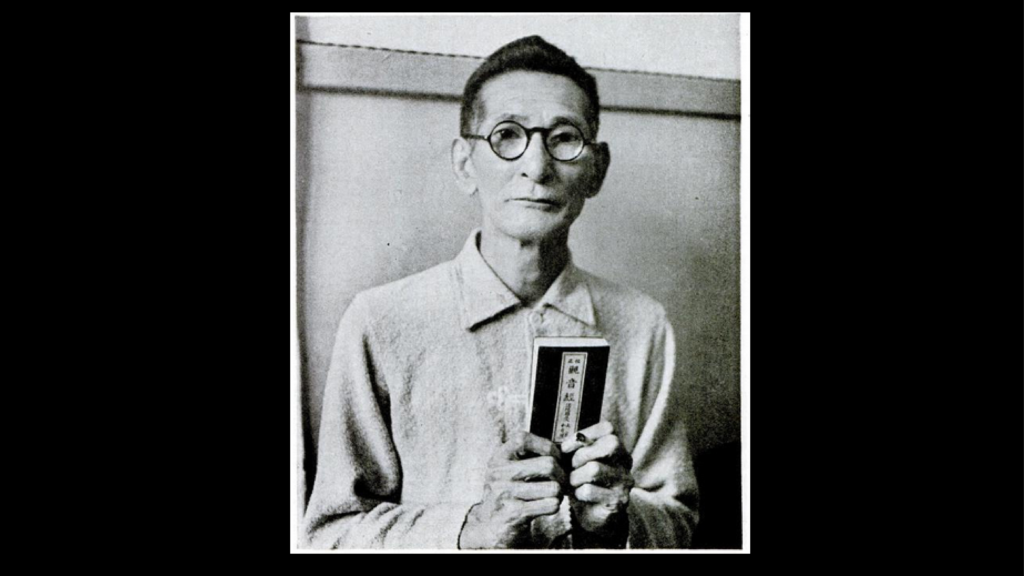

On the first day of Tokyo Trial, Okawa appeared in the court in pajamas and sandals, and slapped the bald head of Former Primer TOJO Hideki, often described as the Japanese version of Hitler. There was a humorous film record of that on youtube. Okawa screamed either “Indians, come” in German or “It’s a comedy!” in English and was removed from the court to be examined. Both U.S. and Japanese psychiatrists diagnosed him with brain syphilis which he allegedly contracted from a geisha 35 years or so prior. He was kept in mental hospitals for the duration of the trial. In the meantime, his pre-1945 books, except privately-owned copies, were pulped and recycled into new textbooks for Japanese school children by the SCAP (Supreme Commander of Allied Powers) under their War Guilt Information Program. Okawa regained health, and translated the Holy Quran on the mental hospital bed, the first complete Japanese translation of the Quran, which remains highly regarded among the Islam scholars in Japan today. By the spring 1947, an American military psychiatrist said he was recovered to stand the trial and he wished to be tried, but was never called back, and released by General MacArthur’s Christmas amnesty in 1948. The dismissal date was the day after the executions of seven other Class-A War criminals, many of them Okawa’s acquaintances, friends, and enemies. We learned years later from the declassified CIA files at the U.S. National Archives that Okawa was under CIA’s close watch until his death in 1957.

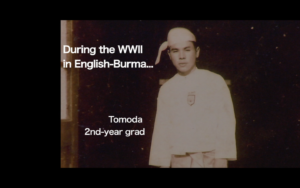

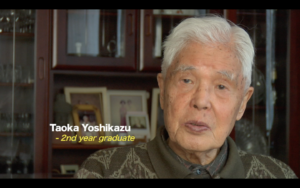

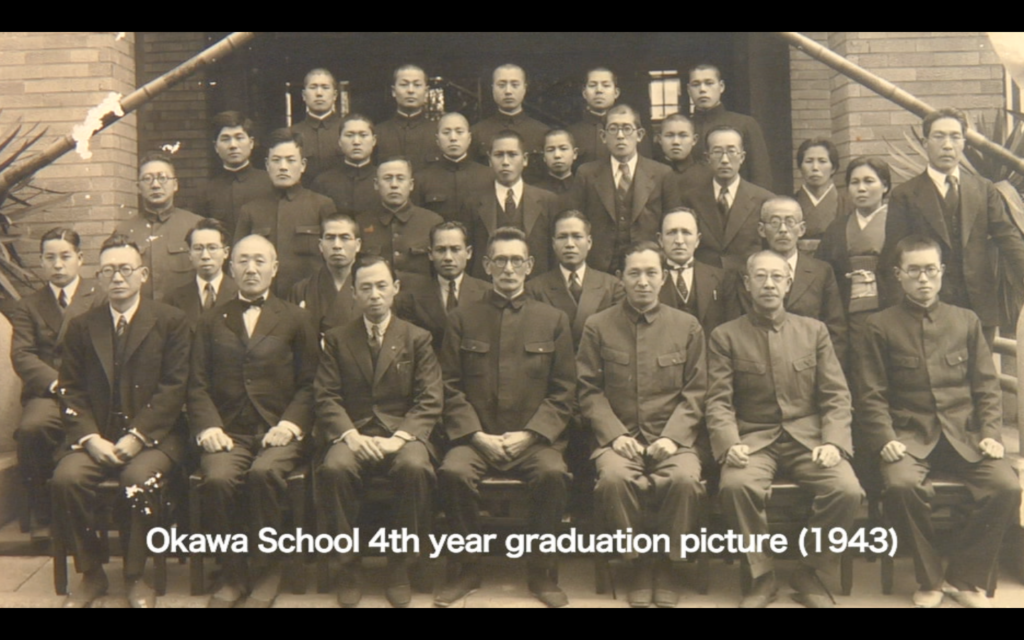

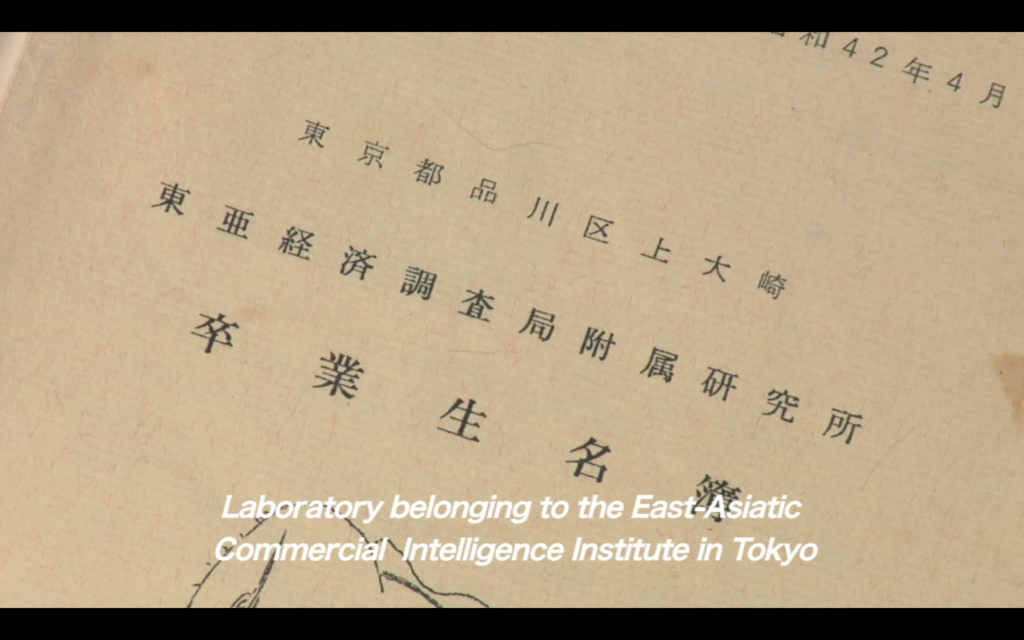

Who was this man? What connection did he have with Max’s dad? Soon, we found that Hideo had graduated from a secretive school called “Laboratory Belonging to The East-Asiatic Commercial Intelligence Institute at Tokyo,” a.k.a. “Okawa Juku (juku= private school),” which was in existence for 7 years between 1938-1945. The school was personally run by Dr. Okawa but funded by the South Manchurian Railway Company, Foreign Ministry, and the Japanese Imperial Army. Every year, ten to twenty boys of 16-18 years of age were selected from all over Japan and were given the elitist education on Asiatic languages, economic situations and cultures. They were sent to diverse areas of Southeast Asia to work as business liaisons for 10 years upon graduation. But they got drafted by the Army before the 10 years and the school was condemned as “a school for espionage” at Tokyo Trial.

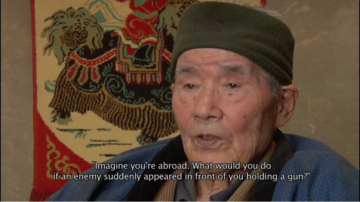

What was Hideo learning at such school, and what was he doing during the war in Asia? He never spoke about it. Was he really a spy? With a mixture of fear of Hideo’s possible ultraright leaning (and possible wrong doing in Asia) and great curiosity, we began approaching a dozen surviving alumni among merely 96 students of the Okawa. They were in their mid 80s and the production seemed urgent. What they said was something totally unexpected – they were taught by Okawa to help the locals in Asia to achieve independence. They were overtly or covertly involved in the underground independence movements across Asia, and worked closely with luminaries among Asia’s independent fighters such as General Aung San (Aung San Suu Kyi’s father) and Ne Win of Burma, Subhas Chandra Bose (Netaji) of India, Ngo Dinh Diem of Vietnam, or Son Ngoc Thanh of Cambodia…. We didn’t know many of those names, but they are national heroes who, if survived the turbulent years, held high governmental positions after the independence of their nations. The students had not told about their feverish passion for Asia’s independence and their experience in Asia outside of their alumni “zine.” We had grown up in Japan with a sense of guilt, and were never taught about Japan’s involvement in Asia’s independence movements. We soon figured that some important parts of history have been hidden from our view. But Okawa’s students also witnessed the cruelties and deception of the Japanese army towards the locals in Asia and the Allies’ POW, and expressed their dilemmas.

How should we digest the fact that the students of a mad war criminal were helping freedom fighters of Asia? The film chronicles our whole journey, in Max’s first person voice, from searching for his late father’s untold past to desiring a dialog among Asians about our past and future.